Genocide

The first genocide of the 21st century was committed against the ethno-religious group of Yazidis in Sinjar (northern Iraq) in August 2014. The United Nations, numerous human rights organisations and states, e.g. USA, Canada, England, Israel, Armenia, classified the persecution and destruction as genocide. The European Parliament reiterated this position with a resolution passed in February 2016. After a successful online petition, the recognition of the genocide in Germany was discussed in the Petitions and Human Rights Committee and recognized as genocide on 19 January 2023 by the German Bundestag. For various reasons, this genocide has not been documented or scientifically processed in Iraq or any other country, nor has it been punished through judicial means. Eight years later, the consequences for the Yazidi victim-survivors are still massive and destructive.

Attack in August 2014

Even before the start of the genocide in 2014, there were repeated repressions and acts of terrorism against Yazidis in the Sinjar province. For example, in August 2007, more than 500 people died in the two Yazidi districts of Til Ezêr and Sîba Şêx Xidir, presumably through Islamist suicide bombers. Until 2014, Sinjar was the world’s largest Yazidi settlement area, with about 400,000 Yazidis living alongside approximately 80,000 Arab Muslims.

In the early morning of August 3, 2014, fighters from the Islamic State (IS, also ISIS or DAIŞ) terrorist militia attacked the Yazidi settlements in the Sinjar province. The Peshmerga, i.e., the military units of the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan, which were stationed there since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, withdrew from the attackers.

With heavy artillery, IS fighters destroyed villages, towns and temples, which they robbed and burned. Yazidi families were divided. Men and those trying to flee were killed individually or in groups, often in front of their next of kin. The victims were buried in over 80 mass graves. In addition, over 6,400 Yazidis, especially women and children, were abducted, raped and enslaved. Within a few hours, around 400,000 people became internally displaced.

The genocide of the Yazidis took place before the eyes and with the knowledge of the international media landscape: calls for help and video clips of the crimes spread via mobile phones and e-mails. Similarly, ISIS perpetrators posted the atrocities on their social media channels for propaganda purposes.

Escape

The attack on the city and the province of the same name, Sinjar, forced around 400,000 Yazidis to leave their homeland. Those who could not escape to the Kurdistan region fled to the neighbouring mountains. There, Yazidis, who often had not even had the opportunity to take their personal belongings or sufficient food and water with them, stayed for several days. Finally, on 10 August 2010 YPG/YPJ units, with the support of other military units and indiviuals, were able to set up an escape corridor to Rojava (northern Syria). Around 50,000 Yazidis could be evacuated. This way, they prevented an even larger massacre of Yazidis by the ISIS terrorist militia. Some elderly and infants did not survive. They died of hunger and thirst in the mountains.

At that time, Yazidis, who had escaped to Rojava (northern Syria), could hardly fall back on organised aid structures since the escape via the corridor had to be organised in a hurry due to the massive and imminent threat. Yazidis lived on the streets for days, and many moved on to Iraq in the following days, where they faced a similar situation. Only after some time could provisional refugee camps be set up in the Kurdish-governed areas of Syria and northern Iraq. Many Yazidis continued their escape via Turkey. In the Kurdish-dominated south-eastern regions of Turkey, primarily the municipalities set up refugee camps in which Yazidis also found refuge, the largest of them in the Diyarbakır region.

Many Yazidis who fled via Turkey made their way to Europe – a life-threatening escape given the criminalisation of passage routes, including by the European Union. As a result, many Yazidis drowned in the Mediterranean, trying to flee the atrocities committed by IS. The authorities took most of those who made it to Europe to other refugee camps.

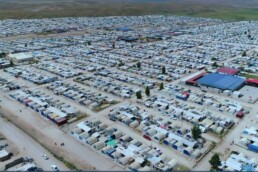

The conditions in the Greek refugee camps are also provisional. The camps are overcrowded, and families are often left to fight for themselves. Germany was the most common escape destination for those Yazidis who made it to Europe. Around 200,000 Yazidis are still living in the refugee camps in northern Iraq.

There are repeated fires in the refugee camps, as here in the province of Duhok/Kurdistan, which can spread quickly due to the tightly packed tents made of plastic. People have died or been injured as a result. Likewise, people lose their belongings they could keep in the confined space, which has psychological consequences. Safety in the camps is not guaranteed due to fires. © Sifian Badel Alias

Enslavement

More than 6,400 Yazidis were abducted by ISIS terrorists. Martyrdom began for them. ISIS fighters repeatedly raped Yazidi women and girls before selling them on slave markets in Syria and Iraq, for example, in Raqqa or Mosul. A survivor recalls her sale at a market in Raqqa:

[I]f any of the men chose us he would raise his hand. The seller from ISIS had [a] paper with our name and the price for us on it. They would give it to the man who raised that hand. Then he would take the woman, or women, to his car and he would go.

— Taken from: United Nations Human Rights Council (2016): ‘They came to destroy’:

ISIS Crimes Against the Yazidis, p.13.

IS members involved in the buying and selling came from countries all over the world. There were fighters from Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, Germany and other Western countries. As the United Nations (2016) explained, IS treats the kidnapped women and girls as so-called spoils of war, which IS fighters claim to ‘possess’. So as soon as a Yazidi woman or girl was sold, she became the ‘possession’ of the buyer. They could be resold, given away or inherited as they pleased.

After they were sold, Yazidi women and girls and small children who were sold with their mothers lived directly with the IS fighters or were housed by them in apartments or houses. Since they were not allowed to leave their quarters, they were usually locked up. Attempts to escape were prevented by denying the captive women and girls the abaya; a traditional Islamic garment women had to wear in public in IS-controlled areas. Survivors report an absolute lack of rights, sexual and domestic slavery, forced marriages, forced conversion to Islam and severe indoctrination. As Tagay and Ortaç (2016) summarise, the exercise of sexual violence is legitimised by IS through a fundamentalist interpretation of Islamic legal principles.

Around 2,600 women and children kidnapped and enslaved by ISIS are currently in the hands of their tormentors or in places where they were sold if they are still alive. In addition, there are isolated cases in which the ransom of a Yazidi woman or a Yazidi child from captivity for horrendous sums of money is successful or missing Yazidis are found in refugee camps.

Mass graves

After IS was pushed back through military means, the extent of its crimes became visible. The terrorist militia buried the victims of its atrocities in mass graves, the largest of which holds up to 3,000 bodies. More than 200 mass graves containing the remains of Islamic State victims have been discovered in Iraq, almost half of them in the northern province of Nineveh, which Yazidis mostly inhabited at the time of the attacks. More mass graves have been found in Syria, with more than 4,000 bodies dug up in the former IS stronghold of Raqqa alone. Despite scientific documentation and forensic research, most of the people whose remains were found in the graves have not been identified to this day. Some mass graves were also set on fire by the terrorist militia and left unprotected from the weather and the local animals so that not all the mortal remains of those killed could be found.

Since the mass graves in northern Iraq contain the remains of the Yazidis killed by IS, their opening in northern Iraq is accompanied by religious Yazidi figures. The dead are ceremonially reburied in Yazidi cemeteries. They are thus granted a more dignified burial.

Destruction of Cultural Property

With the beginning of the ongoing genocide against the Yazidis in Sinjar, the Islamic State (IS) also destroyed sacred towers and temples. The holy sites and pilgrimage places in the Yazidis’ settlement areas are evidence of history, identity and faith. They are spiritual places that unite members of the community. People come here once a year for the main pilgrimage festival and visits in between, especially when people are ill or want to make a wish. For the most part, towers and temples honour people who have done important things for the community throughout history, such as protecting them from genocide and caring for them religiously. Because beliefs are passed down orally, temples also provide evidence of a community’s history and origins. The reconstruction and the inauguration of individual temples started after the victory against ISIS and the return of Yazidis to Sinjar.

The rider of Gêdûk (Sûwârê Gêdûkê) was Şêx Mahamma. […] He was a brave fighter. He protected the Êzîdxan [area inhabited by Yazidis]. […] The Simoqî said they took their tents with them when they went to the pasture. They left all their belongings and gold at the temple of Sûwârê Gêdûkê. Nothing was ever stolen.

— Yazidi survivor about the temple Mahma Reşa. Taken from: Empowering Memory, Women for Justice 2020, p. 10. (freely translated from German)

Resistance and (Power-) Struggles in Sinjar

Although the Sinjar region administratively belonged to the central government in Baghdad even after the fall of Saddam Hussein, the Kurdish regional government had de facto control, maintained through the stationing of its armed units, the Peshmerga, which some Yazidis had also joined. Sinjar falls under Article 140 of the Iraqi Constitution, according to which the population in ‘disputed areas’ can determine its administrative affiliation with Baghdad or Kurdistan through a referendum.

Due to the recognisable danger from ISIS, which had already advanced to Mosul and Til Afer, the Yazidis had built protective trenches in their villages weeks before August 3, 2014. Equipped with light firearms, Yazidi men were on watch 24 hours a day in rotation. After the attacks on South Sinjar began in the early morning of 3 August 2014, Yazidi men fought against IS at the trenches in Gir Zerik and Sîba Şêx Xidir until around 7 a.m., when their ammunition ran out. The Peshmerga stationed in Sinjar withdrew to Kurdistan early in the morning. Yazidis in Germany also joined Kurdish and Yazidi units to fight against IS. Others were connected to Germany through family members. A well-known example is Qasim Şeşo. He joined together with his son from Germany to fight ISIS in Sinjar.

On 3 August 2014, some PKK and YPG/YPJ fighters from Rojava (northern Syria) were able to advance into the Sinjar Mountains. They fought and gathered Yazidis around them who opposed IS in the mountains, trained people determined to fight and coordinated. In addition, there were also armed Yazidi family alliances supporting them. Tens of thousands of Yazidis who IS surrounded were rescued via the corridor to Rojava (northern Syria) created on 10 August 2014, by YPG/YPJ and the PKK forces (HPG and YJA-Star).

In mid-October 2014, IS managed to advance to the foot of the Sinjar Mountains. However, the Yazidi armed units HPŞ (Hêza Parastina Şingal), together with the newly founded YBŞ (Yekîneyên Berxwedana Şingal), were able to hold the village around the holy temple of Şerfedîn.

A Peshmerga offensive in November 2014 resulted in parts of Sinjar City falling into Kurdish hands in December 2014. A major offensive (Operation Free Sinjar) started in the autumn of 2015, during which the Peshmerga occupied important buildings in Sinjar City, while the YBŞ, YPG and PKK mainly engaged in house-to-house fighting. The HPŞ was also involved in this offensive. A Yazidi alliance (Fermandariya Hevbeş a Şengalê) founded in October 2015 between YJÊ (Women’s Unit of YBŞ), YBŞ, HPŞ and other independent Yazidi units later fell apart due to ideological and political differences. The loss of Sinjar City was a serious setback for ISIS since the two most important IS capitals, Raqqa and Mosul, were connected by the highway that ran through it.

In 2017, the power situation changed. US anti-IS efforts brought Iraqi federal forces back to Sinjar, particularly the paramilitary Shia Popular Mobilization (al-Hashd al-Shaabi) groups. After a failed independence referendum by the Kurdistan Regional Government, they recaptured Mosul. They pushed the KDP-Peshmerga out of Sinjar and coordinated their presence with the YBŞ and other Yazidi units.

Turkish airstrikes on Sinjar have been ongoing since 2017. In addition to the dead and injured, members of armed forces and civilians, there are psychological individual and societal consequences. Turkey targets YBŞ leaders, commanders and bases, accusing them of being a PKK branch in Sinjar. Other targets are the security forces of the self-proclaimed government (Kurdish Asayîşa Êzîdxanê) or buildings of associations close to them, such as those of the autonomous self-government of Sinjar. Parts of the YBŞ have joined the predominantly Shia so-called People’s Mobilization Units (PMU), recognised by the Iraqi state as part of the regular Iraqi Army (80th Regiment). A Turkish airstrike destroyed the hospital in Skeniye in August 2019, killing seven people and damaging farmland.

The Erbil-Baghdad agreement signed in October 2020 provides, among other things, for the armed Yazidi units to be replaced by Iraqi forces, which repeatedly leads to tensions and clashes between YBŞ and the Iraqi army because the former do not want to give up their bases.

The ongoing insecurity is preventing many in the refugee camps in Kurdistan from returning to Sinjar. Many Yazidis who had already returned had to flee to Kurdistan again due to fighting or air raids.

Fighters and civilians killed in the fight against IS or by Turkish airstrikes are revered as martyrs by Yazidis, Kurds and Arabs. Their pictures and statues can be seen in public places such as main roads, roundabouts or private buildings. The YBŞ/YJÊ has created its own martyrs’ cemetery in Kersê. There are numerous songs about Yazidi, Kurdish and Arab units and fighters, poems and songs about martyrs. Many martyrs are commemorated on their anniversaries or during events.

Yazidi resistance fighters © Sifian Badel Alias

I can swearthat nobody was braver than youAs the brave one, you remain in our thoughtsThe spear of resistance and defenseYour monument at the Skeniye water source will one dayBecome the pilgrimage for the youthand be a symbol of heroic deeds.

— Excerpt from Hecî Qîranî’s poem ‘Şêrê Skêniye’ (‘Lion of Skêniye’),

in memory of Şêx Xêrî, who had joined the fight against IS and was killed in October 2014.

Translation, 2nd verse

(freely translated from German)